(Ensayo de Transferencia) Photos courtesy of 45 SNA

Sound art researcher Brandon LaBelle suggests that ivisibility operates in the possibility of breaking apart the linguistic structures by detaching the signifier of the sound from its signified. The idea of the acousmatic has been applied to keep the identity of activists-artists secret and to conceal or reveal elements of a certain soundscape as part of activist strategies. Imperceptibility is a term that I will use in connection with what LaBelle refers to as invisibility, in which manifestations of great agency function through disseminated and subtle structures which are impossible to detect. There is a passage in the book The Great Animal Orchestra by Bernie Krause that I would like to associate with his study of the politics of sound. After exhaustive research, Krause learned that the scaphiopodidae frog species relies on sound spatialization and unison singing to survive encounters with predators by creating a surface of sound which acts like a shield where no individual frog can be localized and hunted. Nevertheless, interference from aircraft noise pollution can break down these alliance structures created by the frogs, which find in their openness to the sounding environment their major strength and vulnerability. This analogy illustrates how resistance operates in LaBelle’s theories, where the separation between strengths and weaknesses are often indistinguishable.

María Leguízamo is an artist from Colombia who presented her sound installation “Ensayo de Transferencia” in the 45 Salon Nacional de Artistas, a massive and powerful piece that earned positive comments from editors, curators, fellow artists and visitors. The 45 Salon Nacional de Artistas was one of the biggest art events in Latin America in 2019, featuring the work of 160 artists, and María’s piece was presented in Pastas el Gallo, an abandoned building which was formerly a food plant.

DV. In an interview, I heard that one of the first things that you did during the creative process of the piece, was listening to the street sounds around the building. You said you noticed a lot of market shouting or “pregoneo” and “perifoneo” resonating on the nearby streets. In which way this experience with public space vocal sounds influenced the conception of the piece?

ML. My first visit to Plaza España (after the invitation to participate in the show) was determinant to the piece. I sat in the plaza and the fist thing I felt was the sound of home recorded commercials by street vendors selling cellphone accessories. I liked the idea of a square being flooded by anonymous voices and their echo, as opposed to hearing an amplified person and their amplified voice. Yes, I’m talking about tension between voices of power and anonymous and apparent non essential voices and messages. I initially wanted to make a sound sculpture for the plaza, inspired by these home recorded voices/commercials, but the idea paradoxically didn’t thrive given the requirement of licenses and permissions to occupy public space.I began thinking about political discourses and podium speeches. I studied them and got obsessed over the image of a president giving a speech and unknowingly leaking urine while speaking. I finally kept the voice and sound as the the main path to develop the final piece but it changed radically.

I had to pause the president’s project because I don’t like being misunderstood and the political climate at the moment would have allowed for a lot of it. Also, my spirit was emotionally devastated and I felt like it was more real and honest to devote the project to something that was closer to was I was experiencing at the moment. I felt it was dishonest to ignore that impulse and recently talking with one of the curators, William Contreras, we realized all artists involved in the project took the “affections” path. President leaking has to wait for now.

I started listening to sounds inside and outside the abandoned factory. I was also writing a diary and trying to capture that inner voice that we all keep “hearing”, trying as well to understand it in relation to the others voice: it is the same. I could remember snippets of human voices around the factory and that sounding memory blended necessarily with my unspoken voice. We don’t realize it the whole time but we share a lot of mind space with a lot of people we don’t necessarily know.

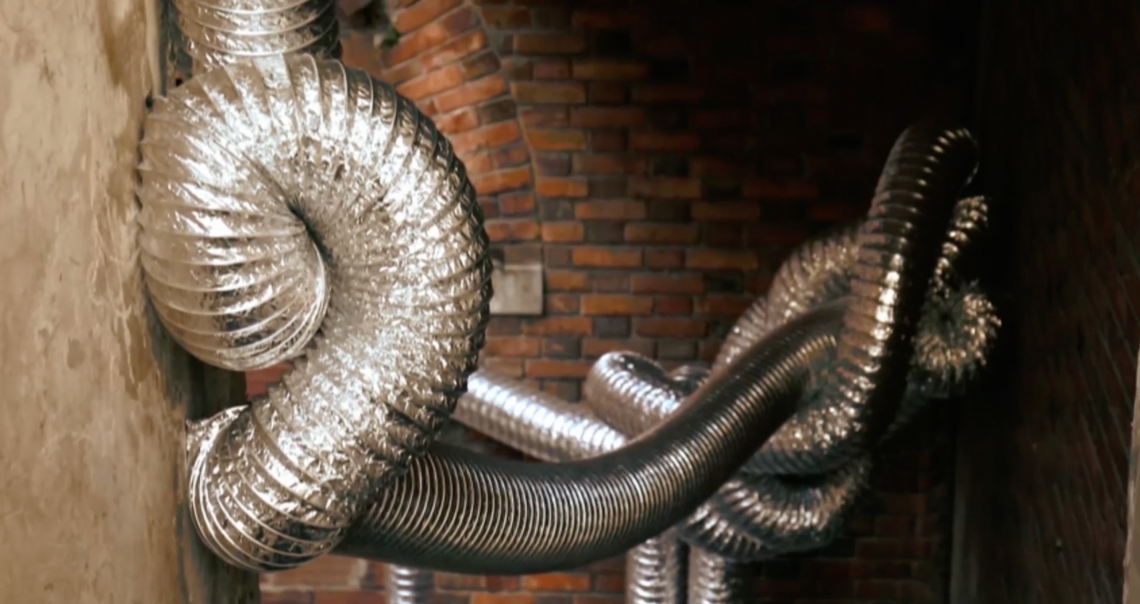

I walked around the streets of Plaza España and heard fragments of conversations, complains, orders, grunts, that blended with my stream of inner thoughts. That happens to all of us, right? This process of note taking and ear widening eventually lead to the necessity of making a speaker like a body for these voices. The first intuition looked like a small tunnel that could break through the building, like a parasite. Later, when I found the aluminum ducts that ended up making out the piece, I realized I was looking for a tripe, an intestine, a gut.

An organ that over flooded a body, exceeding it, surpassing it with its vibrating presence.

(Ensayo de Transferencia) Photos courtesy of 45 SNA

DV. This is your first time working with sound but your interest in sound has previously reflected in some of your texts. In which way creating “Ensayo de transferencia” has changed your interest and approach to sound?

ML. Is the first piece conceived to be a sound piece but I’ve flirted with sound since I remember. The first time I used it was as documentation of an action or performance piece I wanted to keep invisible but maintaining the landscape and trajectory of movement somehow. I was interested in the way sound could create a portrait of the place (which was very important to the piece) and a feeling of linear movement like a drawing of a line connecting two different places. “Ensayo de Transferencia” ended up being a sounding body because some time before I became aware of how sound can occupy public spaces in an apparently innocuous ways and create architecture without being visible and robust presence. Just now a protest march is passing on the street and the windows of my apartment are vibrating.

Along the process of working with the gut and thanks to Camilo Rojas, the sound artist that helped me composing and editing the sound tracks, I started to actually see the way sound can affect matter. I knew about this but it surprised me how visible and powerful it can be. Thanks to Camilo, I learned some of the hardware that sustains and carries sounds. I learned how to connect copper cables to speakers, amplifiers and electricity. That was awesome and I’m endlessly grateful for it. From there, I decided I was going to start working with the “materiality of sound” as part of my sculptural and poetical hunts.

(Ensayo de Transferencia) Photos courtesy of 45 SNA

DV. The “gut” propagates across the building and creates a connection between the different rooms, which reflects some of the most notorious acoustic properties of sound. Is this connection important for you?

ML. I never thought about it that way but it’s beautiful how you name it and suddenly becomes important, yes. Although, I think that that quality of bridge or tunnel that connects different spaces and/or stances, better reflects on a deep longing I have for merging, union and deep contact between contrast and discrepancy. None the less, thinking about a speaker that could carry the sound along the whole factory was determinant since I also thought about it as a sort I company (sometimes shy, sometimes loud) for the exhibition tour.

DV. You mention how you are interested in the “erosive” potency of the voice. Can you tell us about how this idea is reflected in the sounds that you used to compose the audible element of the piece?

ML. This question is perfect to introduce what’s in the marrow of my practice. I remember wanting the sound to blend with the usual sonic landscape of the place and I began with the voice of the doves that seem irrelevant but are the beings that actually dwell in the factory. I didn’t want to imitate their sound but to talk to them, so I started recording melodies I sing to myself but in a dove registry. The composition ended up being very intuitive and insecure on my end. I always kept the agenda about using the erosive quality of sound but I didn’t compose the tracks thinking about that. There are moments of the piece where repetition and a seemingly scratched disk emerge like scratches or continuous rubs over surfaces, like water over a stone or hands over a statue. That did happen but it wasn’t that clear to me until you asked.

I told you it was an excellent question to begin speaking about the core of my research because erosion is one of the main foundations of my work and also, one of the embodiments of Impoder.

(Ensayo de Transferencia) Photos courtesy of 45 SNA

DV. You mention that you are interested in the way in which the sound waves propagate through solid matter and transform it in imperceptible ways, and you link this phenomena to the idea of “impoder”. What can you tell us about your experience working with the invisible, and often neglected, presence of sound in order to develop your interest in “impoder”?

ML. It is Impoder, what develops my interest towards sound and not the other way around. It is my interest in the invisible, most fragile and often neglected what brings me to the sound’s arms. My undergrad thesis geared around the idea of finding strength and ultimate potency in the most fragile and apparently irrelevant. I decided to make an almost visible horizon made of one single thread of human hair built by countless hairs knotted together and donated by different people. One body made out of different bodies. Making that sculpture (Uno, 2012) that was also a drawing drove me there: to the necessity of naming a different kind of power whose capacity of transforming radically, lies precisely in its own difference with the dominant power. I used the spool of hair to join two separate ends of a street called “La Calle del Divorcio” (the street of divorce or the divorced street), curiously placed between the building of Bogotá’s Capitol and San Vitorino, beginning at the southwest corner of the main power square of Colombia, la Plaza de Bolívar. Remember that first time I used sound to document an action? Well…

I had to write a text about the project in order to graduate and I couldn’t find a word that could name what I thought was the most important lesson of the process. I went through the dictionary and couldn’t find anything like that. That’s when I decided to venture a new word and send it to the Language Academy of Colombia. The word implies a kind of power, o rather potency, that propels itself from its own fragility: its own crack, its own irrelevance, its own shadow.

That’s why erosion and other kind of invisible forces are so important. Sound, like a single thread of hair, can seem unsubstantial and harmless, but their power dwells in that same “seeming”. Everything we touch changes imperceptibly every instant, but we can only see the transformation after a long time or an intense repetition of that touch.

Sound, the same way as wind, persists through vibration and a continuous of touches. You could say they the Impoder of some sounds comes from its own lack of matter, and following that idea you could also say that “it doesn’t matter”. I’m deeply interested in the undeniable transformation – yet invisible- implicit in that phenomena. And not only because it’s physical behavior but because of the “content” that the sound carries. That’s why I’m interested in the human voice and the capacity of erosion that specific words and ideas can have on solid and concrete structures. Materially and spiritually.

(Ensayo de Transferencia) Photos courtesy of 45 SNA

DV. Could you mention books, articles or art pieces that were influential or relevant for you in the creation of “Ensayo de transferencia”?

ML. The most influential conversation I can recall from the time I was conceiving the piece was the one I had with my dear friend Kara Springer. She told me that sound keeps reverberating eternally in the place where it was produced. I never researched profoundly about this but that idea was very present, and still is, while making “the gut”.

Another important company I had was the poems of Raúl Gómez Jattin, a Colombian poet that often inhabited the street. He wrote images like the following (my rough translations):

______________

Take my hand,

Caress it carefully

It is freshly cut ( or wounded).

And

Incantation

The inhabitants of my village. They say I’m a man despicable and dangerous And they’re not very wrong Despicable and dangerous That’s what has made of me Love and poetry Respectable inhabitant Don’t worry

That only me I usually hurt.

and

Because I bow to whoever gives me

a few granadillas or a smile from their inheritance Or just because I go where the sturdy inhabitants are to beg for a coin or a shirt and they give it to me Because I watch the sky with the eyes of a hawk And name it in my verses. Because I’m alone Because I slept seven months in a rocking chair and five in the sidewalks of a city

Because I look at wealth sideways

but not with hatred

and

I defend my self

Before devouring his pensive gut

Before offending him with and word and gesture Before tearing him down

Value the madman

His undeniable propensity for poetry

His tree that grows through his mouth

with roots entangled in the sky

He represents us before the world

with his painful sensitivity like childbirth

___________________________________

Also the permanent echo of Antonin Artaud was a crucial company through the making of “the gut”.

(Ensayo de Transferencia) Photos courtesy of 45 SNA

To hear and see more about “Ensayos de transferencia” watch the video in the following link.