Interview with Richard Allen from A Closer Listen

by David Vélez

Reviewing non-mainstream music is not always an easy task: it is not usually paid and demands plenty of time, focus and inspiration. Music reviewers probably listen to more music than anybody else so I thought it could be interesting to know a bit further about Richard Allen from A Closer Listen through an interview. ACL is a journal that focuses on different manifestations of music, and among them we find recordings-based compositions and sound art. A Closer Listen represent an important voice in this line of work of with a multitude of reviews posted on this regard.

Q (DV). How A Closer Listen started? Who was involved and how it was developed?

A (RA). A Closer Listen began with a trio of principles: kindness, communication and partnership. Kindness is finding something nice to say about everything we review. Communication is answering all personal emails. Partnership is making decisions as a team. The site name indicates the way we approach reviews. Nothing is ever assigned. If a staffer hears a release and thinks it is worthy of a closer listen, then he chooses it for review. Everyone on the staff contributes in a different way. First are the three administrators. I write an average of a review every day and answer the mail. Joseph contributes an amazing array of mixes, many of which he produces himself. Jeremy is our electronic specialist and technical expert. The other staffers all have their own area of expertise ~ generalizing a bit, James specializes in ambient, Mo in dark ambient, Nayt in album art, Zach in cassette culture, and David in experimental music. Our latest staff member is Chris, who specializes in modern composition. Many of our writers are also artists, which plays into the idea of kindness; we hope that we are seen as a friend of artists and labels as well as a resource for fans.

Q. Why did you decided to have a special section to write about compositions based on field recordings and soundscapes?

A. Our specialties are instrumental and experimental music, and sound art is one of the most fascinating fields around. We feel that those who are interested in any of the other genres we cover (post-rock, drone, electronic and more) may also be interested in sound art. We are also interested in the ongoing conversation about what constitutes music. John Cage considered every sound to be music, but my own opinion is a bit more specific; I believe that every sound can be considered music in the ear of the beholder. Nature may sound inherently musical to some, despite its lack of intention. A whale may be singing a song, but a bird may simply be communicating through a mating call. We call it “birdsong”, but that’s our own projection.

Q. Do the ACL editors have a different approach when write about field recordings-based works than when you write about say ambient, improv or electroacoustic?

A. The approach is pretty much the same. On a visceral level we need to like it in some way, whether through enjoyment or intellectual interest. In writing we try to convey excitement, knowing that the general public is less aware of field recordings than of rock. For example – and I’m sure you’ve encountered the same thing – I tried to explain field recordings to a co-worker this past weekend. His response was, “Oh, I have a CD of a rainstorm that I got at Wal-Mart!” So the challenge is in trying to increase interest in a valuable field, which is an uphill battle. I’ve found that in conversation, the best approach is to be specific: “I have been listening to some really cool sounds lately: two guys who got lost in the Amazon rain forest and recorded what they heard, an artist who went to Iceland and edited all of her favorite sounds to half an hour, another who lowered a microphone into a volcano.” The challenge for the artist and the reviewer is to lead a person who owns only one (not very good) field recording to consider another, and to lead a fan who owns ten thunderstorm recordings to purchase more.

Q. Today we see a multitude of ways to work with recordings, from the more documental approach to works where the recordings are heavily modified. How do you consider these differences when you review these kind of works, both formally and conceptually in terms of the purpose of the artist and the final result?

A. I’m a fan of both. I find huge value in the Sound Mapping project taking place throughout the world, especially when it comes to capturing the sounds of endangered sonic environments, whether they be man-made (the last sounds of a crumbling medieval church), human vocal (disappearing dialects) or natural (endangered species, forests about to be cleared, spaces threatened by sonic pollution and physical encroachment). But modified recordings can be invaluable when it comes to dynamic contrast: bringing a subject to life by manipulating the sounds, durations of sounds, and placement of sounds, or even adding instruments in order to tell a clearer story. For example, a 12-hour recording of a night spent in the jungle might be accurate, but a 1-hour edit might be more effective. I often wish recordings were made available in both formats simultaneously: a 24-track, 70 minute album of sources and one 50-minute mix.

Q. What would you say is the hardest part of keeping A Closer Listen as active as it is, and what are the aspects that make you happier and more accomplished about your work at ACL?

A. The hardest part is writing to artists and labels whose works have not been picked up for review. Everyone in the industry seems to be working hard with little payoff, and we wish that we could review everything that gets sent in. The truth is, we like almost everything, but we only review what we love and have time to review. On the positive side, there’s a tremendous sense of accomplishment that comes from knowing we’ve been able to help support the music that means so much to us.

Q. How is your relation with the labels and artists whose material you review?

A. I’d characterize the relationship as friendly, especially since most people understand our time and space constraints. It’s even better when we review a release and hear back from the artist. This makes a huge difference to everyone on the staff. We may be reviewers, but we’re really fans first, and no matter how old we get, we’re always a little amazed that we’re able to have a dialogue with the artists and labels we love!

In regard of sound art and composition and their future Richard added:

(RA). While I think there will always be a place for unmodified field recordings, I also feel that there is a great future for sound art and the incorporation of sound art in the wider arena of music. Many artists (especially in the ambient, electronic and experimental realms) are discovering the huge difference between sound effects and sound art. For decades, musicians wanting ambience in their recordings just grabbed a sample of rain (The Who, “Reign O’er Me”), but recent works have seen a wider and more specific use of field recordings. By incorporating such sounds throughout their works, musicians call upon a wider range of sources. Darren Harper and Jared Smyth’s album “Home” was comprised of equal parts instrument and field recording: the sounds of their own homes made the entire project seem more authentic. In like fashion, as artists continue to incorporate the sounds around them, from miked piano (Hauschka) to cutlery (Pawn), the genres will become even more mingled. My home is that this will cause a ripple effect, increasing interest in everything from field recordings to sound installations. In an ideal world, this interest would then expand into an awareness of noise pollution and the importance of preserving sound habitats, so that the last “square inch of silence” would not disappear from our planet.

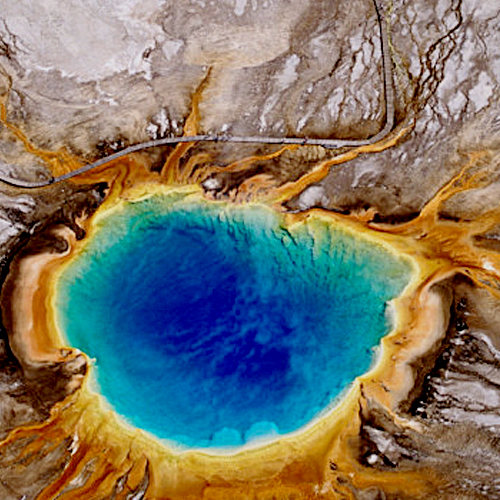

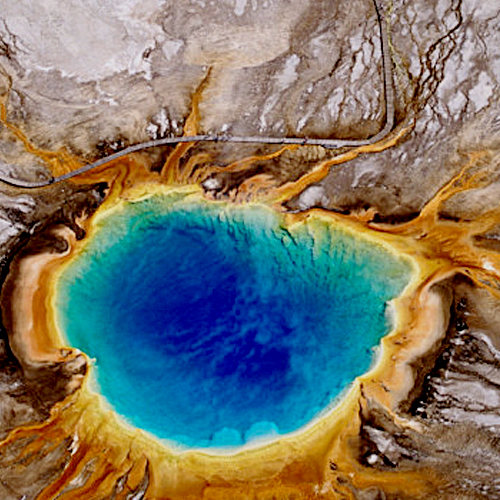

[Upper image: The Grand Prismatic Spring; courtesy of A Closer Listen]